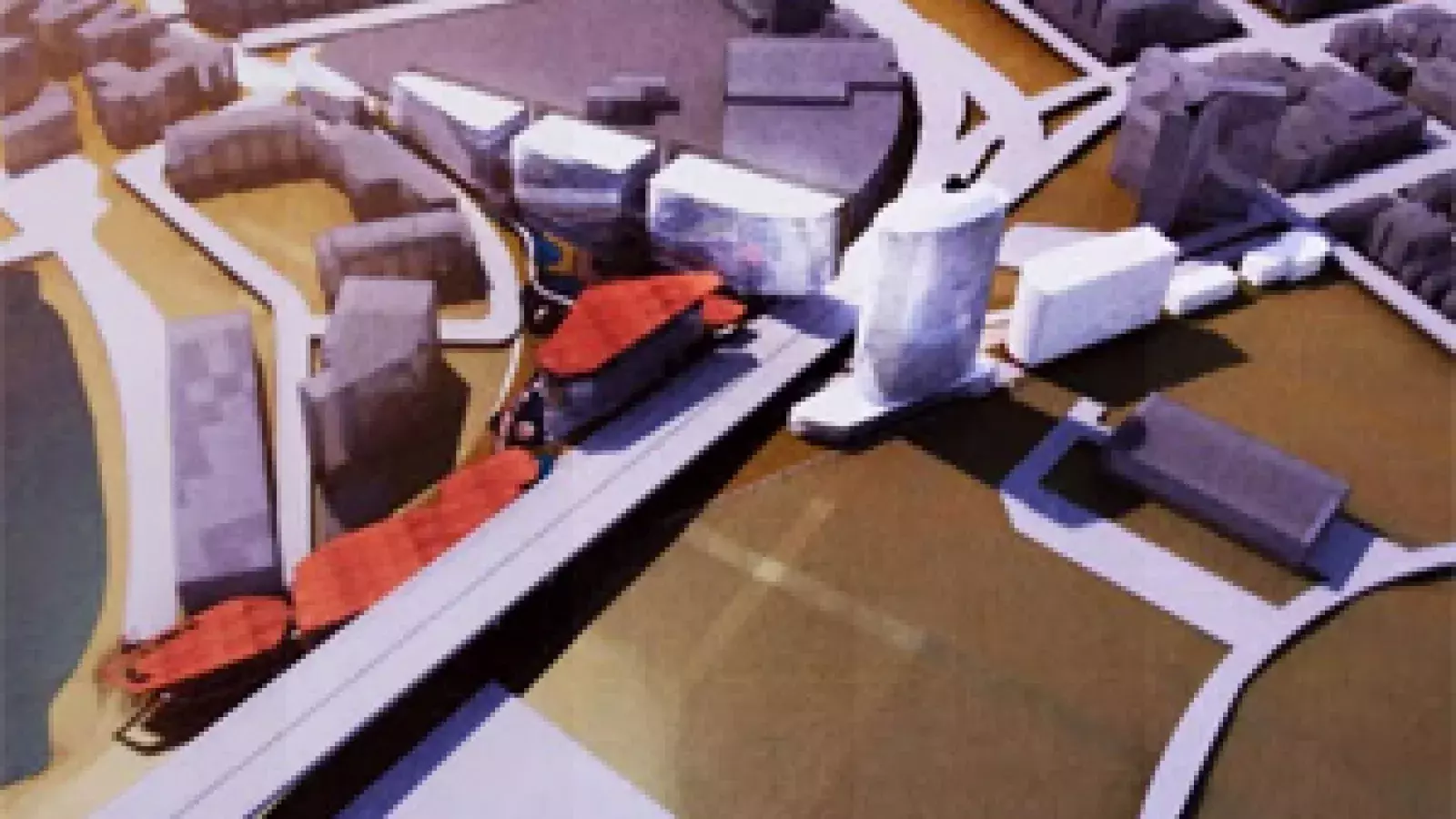

It is among the last open stretches of undeveloped city waterfront. With a density that rivals the Olympic Village, and no requirement for city approval or input, the development of prime waterfront real estate owned by the Squamish Nation is being proposed at the south end of the Burrard Street Bridge. Details are limited; however, initial drawings done by Kasian Architecture illustrate that the $1-billion, two-tower, 2000 parking spot, mixed-use residential community will block the city’s carefully preserved ocean and mountain view corridors and dramatically densify quiet Kitsilano.

The Squamish Nation reclaimed the land in 2002 after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled that, as compensation for forcibly taking the land for railway use and displacing villagers in 1886, the Canadian Pacific Railway should return the land to the band. Stretching from Granville Island to Vanier Park it is an odd-shaped narrow piece of property bounded by Cornwall and bisected by the Burrard Street Bridge. To get an exact location of the site one only has to drive south across the bridge to see a large flashing billboard punctuating the skyline which serves as a constant reminder of the proposed location of a 35 storey high rise.

The Squamish Nation intends to wear an unfamiliar hat in this project – that of developer of the 8.67 acre parcel. In addition, the land will be developed at the Squamish Nation’s sole discretion, requiring no city approval since it is located on reserve land. So far, the public amenities—parks, art galleries, schools and transit plans—typically required of all new city developments of its scope are absent from its design. That’s because none of Vancouver’s celebrated urban design principles apply on reserve land.

All this brings into sharp focus the future of real estate development in Vancouver because far more is at stake than a pair of view blocking condo towers and added traffic congestion. Both the Squamish Nation and the Musqueam Indian Band own numerous undeveloped city lots and large portions of waterfront in Vancouver and North and West Vancouver. Other bands have interest on federal lands—old city army barracks and post offices. In fact, with Vancouver’s downtown largely developed, local First Nations will be huge players in shaping the city over the next 10 years.

Which brings us to the major issue: with no legal tools to control building height or density, municipalities have much to fret about as they will have little control over what is built on these lands or the appropriateness of these developments to the community at large. For some, this is poetic justice, for others this is great cause for concern. However, there is another equally important side – in order for Vancouver to remain one of the best places to live there needs to be careful design and planning on all new developments irrespective of who is building them. It is extremely shortsighted thinking to not take this simple fact into consideration.

It is my hope that the Squamish Nation, and other bands to follow, will want to build on the strong foundation put in place over the decades by our planners, designers and community members. That they will work to create a balance between big profit and good urban design principals. And that they will take into consideration the desires of their neighbours and develop responsibly into the future so that we can all live in a Vancouver we can be proud to call home.

Kim Robertson